Behind The Tomb

- Setken

- Oct 7, 2024

- 10 min read

Updated: Apr 10

[updated 26/2/25]

This essay documents the behind-the-scenes adventures of my research that I began in early 2017 into David and Annabella Syme’s monumental, heritage-listed tomb in Kew Cemetery (a.k.a. Boroondara General Cemetery), Melbourne, Australia. The tomb was built 12 years before the discovery of King Tutankhamun's tomb, when a whole new wave of Egyptomania swept the world. It remains one of the most stunning examples of Egyptianising architecture in the world.

Six paintings, two talks, and one paper later, the project really took on a life of its own. I hope to give you an idea of what motivated me to undertake such a project, illustrate some of its complexities, and conclude with the questions that remain unanswered.

David and Annabella Syme's tomb

Photo by the author

Last year, my talk A Monumental Egyptian Tomb In Melbourne was delivered as part of the audience engagement program for my exhibition Adventures In Zoomorphic Idolatry. The newer, longer version[1] has been rewritten to feature new information including the tomb architects and craftspeople, and especially the spiritual life of the person for whom it was built, David Syme.

This essay tells the story behind that story, and the unearthing of some truly fascinating facts that emerged from it.

Looking for the plans

My initial search began with looking for the plans for David and Annabella’s tomb. I had a very clear idea of the painting I wanted to make based on the drawings (blueprints were not yet customary at the time the building was created commencing 1908), and whilst I could only assume that they existed, the below excerpt from Public Records mentions them, specifically in relation to the revised version shown the trustees in March of the year of Mr. Syme's death.

The minutes of the trustees meeting that mention revised plans for David Syme's tomb ("vault") were presented by architect

Walter Butler, agreed on by all, with details to be finalised by Annabella and fourth son Geoffrey Syme.

(Syme Family Papers, Series VII, estate of David Syme, 1908)

Photo by the author

I got a sense very early on that this was not going to be easy, because at the time of embarking on my research, two completely different architects had been credited with the creation of the monument.

In the new version of my talk I tell this tale because it is curious indeed, but what it amounts to is that there was a period that I estimate from somewhere between the last of the original trustees dying (Oswald Syme, David Syme’s youngest child, in 1967) until roughly late 2017, when I brought it to the attention of the Heritage Department, when the tomb’s authorship was not publicly entirely correct. The actual architect, Walter Richmond Butler, was not credited and another individual was!

Architect Walter Richmond Butler (1864 - 1949)

c1902, from Cyclopedia of Victoria, Vol I, p. 383

It is important to note here that the only references in the easily accessible public record (i.e. the internet) attesting Butler and Bradshaw's authorship was / is Dr. Harriet Edquist's "He Who Sleeps In Philae" paper and the website of Veronica Condon, made for her father Geoffrey Syme. This website has since been disabled.

The misattribution has unfortunately led to some papers being published with the incorrect information, and could most likely have led to a misfiling of the tomb plans and related information as a result.

Impatient, I began painting the first triptych regardless. It was unveiled at my debut solo exhibition in 2018, along with the first examples of my research in the form of information panels displayed at the exhibition.

Memorial I, II and III

February 2018

Go here to see sizes, composition

Above 3 photos: The earliest genesis of my research - info panels at my exhibition NeoPharaonic in February 2018

A monumental historical Melbourne figure: David Syme

David Syme c1856

Photo: National Archives of Australia

In March 2017 when I laid eyes on the tomb for the first time I knew something unique was in play. The structure is a glorious example of not only what funeral stonemasonry could achieve in the 1800’s, but also the Egyptianising expression of it.

As I couldn’t find the plans, I began researching the figure of David Syme. Having read all four biographies of the man, to say that he played a significant role in the establishment of Melbourne is an understatement.

He was the owner and editor of the mighty The Age Newspaper, and frankly, without him, Melbourne would not be what it is today.

I had learned of David and Annabella’s interest in Spiritualism. David was a committee member of the Melbourne Spiritualist Union and Annabella was a member also.

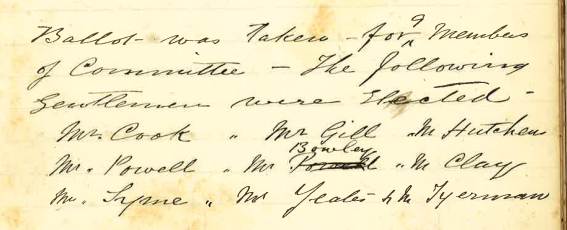

From an entry in the minutes of the Victorian Association of Spiritualists Oct 1870 - Feb 1873 in which David Syme (bottom left) is appointed as a committee member in 1872; it was at the VAS that he met Alfred Deakin

This led into taking a closer look at the period of the mid-1800’s and the century that followed. Spiritualist, and soon to follow Theosophical ideas flooded Melbourne, as they did in the US and Europe too.

David Syme wrote four books, and the final one, The Soul: A Study and An Argument is telling. It's hard to find and not an easy read, largely owing to the vernacular it is written in; yet persisting with it yielded fruit.

It was here that I understood that David Syme knew about the concept and spiritual understanding of soul anatomy - a topic not at all well understood, and hardly written about at that time - and this can't be dismissed in relation to the tomb that he was interred in.

Whilst many civilisations of antiquity had ideas about soul anatomy that seem in stark contrast to our simplified and heavily monotheistic influenced understandings today, it was Ancient Egypt that seems to have possessed the most sophisticated – if not complex – understanding of the topic.

They posited that 9 elements comprised man’s occult anatomy and it was E.A. Wallis Budge that made the first attempts within Egyptology to articulate these.[2]

The tomb of John Herbert and Ethyl Syme in Box Hill Cemetery.

John Herbert was the eldest of the Syme siblings and was interred here in 1939;

a version of this structure has appeared in 3 of my paintings

Researching the people surrounding David Syme produced results (especially Alfred Deakin). His eldest son John Herbert had a smaller tomb in Box Hill continuing the Egyptian revival Ptolemaic / Roman theme (see photo above).

The artisans: Butler and Bradshaw, Mabel Young and the Ballantine brothers

By far the most challenging aspect of my research was in locating and trying to ascertain details, records and the legacies of those responsible for building the Syme tomb.

Architects Walter Butler and Ernest Bradshaw’s legacy is not as celebrated these days as it should be, given their contribution to the architectural landscape of Melbourne then and, especially in Butler’s case, his near-celebrity status.

There are two well-written theses on Butler – both requiring special access privileges to view as they are not yet digitised – but in the case of one, the tomb is omitted. In my discussion with the author, he said that he must have been under the impression at the time of writing (1971) that it was not of Butler’s design owing to the previously mentioned misattribution.

Mabel Young (1875 - 1957)

Photo courtesy Lilydale Historical Society

Mabel Young was responsible for the considerable amount of copper and iron elements in the tomb. Not to be confused with the Irish painter of the same name and period, her specialty was woodwork and metalwork, and she belonged to the Arts and Crafts movement.

As Butler was a member also, it is likely here that the two first met. Like many women artists of the time, Young was overshadowed by her famous husband Blamire[3], and records omit artisan authorship for buildings, referring usually (but not always) only to the architects involved.

Trickiest of all is the legacy of the Ballantine Brothers, Alexander and George, the stonemasons responsible not only for David Syme’s tomb but the spectacular Springthorpe Mausoleum adjacent, completed only years before Syme's.

The Springthorpe Memorial, completed in 1901 by the same stonemasons (A and G Ballantine) of David Syme's tomb; architect Harold Desbrowe-Annear belonged to the Arts and Crafts Society along with Walter Butler, where they formed the T Square Club.

The glass shield around the marble sculpture sarcophagus in the centre is long gone, but the monument has recently enjoyed a spectacular restoration. Photo courtesy Victorian Collections.

It does not help that the brothers appear to have used two versions of spelling in their surname (the other is Ballantyne). The records show that they bequeathed the business to son and nephew Archie Ballantine; not long afterwards, they disappear from the public record.

This does coincide with the decline of enthusiasm for monumental funereal masonry, and the rise of cremation as a preference over burial. However, it does not explain the absence of their archive. Surely the master craftsmen responsible for those divine granite capitals on Syme and the sculpting of the Doric Springthorpe kept records - where are they?

None of the institutions I searched, from Melbourne University to the PMI Library and every archive in between, have them. I am certain that if they exist – and I really hope they have not been lost or destroyed – it will solve the mystery of the authorship of the tiles (discussed below) and the nuances of the tomb including the unseen burial crypt.

My diptych of 2023, "The Soul And David Syme I and II" included my fourth and fifth attempts at capturing the essence of the monument, complete with the Gilles and Marc statue that currently sits outside of the Chirnside Shopping Centre in Melbourne's outer suburbs.

Unanswered Questions

I attempt to answer many questions surrounding the tomb and provide evidence and examples of my research in the talk, while acknowledging that many mysteries remain around the monument.

I have something to say about David Syme’s interest in what we refer to today as Kemeticism, with Butler’s letter to Annabella Syme as a starting point. As far as the greater subject is concerned, it is not the only evidence.

His involvement in Freemasonry has not been resolved, and there is discussion about this in the talk also.

In Reminiscences Of Ages Past (published 2003), Jennifer Smyth states on page 1 that letters between David Syme and Alfred Deakin are in the Smyth family's possession; to my knowledge, Deakin's family have not published theirs or released them to the NLA (where most of his papers and diaries are deposited).

As the two met at the Victorian Spiritualist Union, and had in common an interest in spirituality outside of the "acceptable" conventions of the day, these would provide great insight.

I would like to know when the gates were added to the tomb. We know that this was an extra cost that the trustees bore according to Veronica Condon's website, where she adds that the addition occurred later owing to the number of people walking through the structure.

Syme Memorial gate

Photo courtesy Anthea Palmer / Jimmy Hornet Magazine

The Egyptianising pharaonic heads are problematic in the message they convey within Egyptian symbolism. This is a reference to the pharaoh (the striped nemes headcloth was an insignia of that office).

Did Walter Butler sanction these? His letter to Mrs. Syme describing the monument's symbolism, dated 25th November 1910, was written after the tomb was complete. He mentions that the gates are in place[4]. There is no mention of the pharaonic head as one of the symbols, however.

Walter Butler was a friend of William Lethaby who had authored Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, surely a must-read for the likes of Butler who was later to become the principal architect for the Anglican Archdiocese in Melbourne.

The book warns of avoiding the "architecture of tyrants" and I feel certain that Butler did not wish to convey that David Syme was a megalomaniac, even though one of his common nicknames was King David.

The serpents are identical to those at the top of the structure, so Mabel Young must have been involved, but who did the design with those pharaonic heads, so out of step with the spiritual symbolism of the tomb otherwise?

The stunning and elegant tiles[5] of the tomb have weathered the most out of all the elements of the entire structure, and restoring them will, I imagine, be the most challenging part of any future restoration project.

My tile renders for Memorial I (see complete painting at beginning of post at top) were based on Polaroids taken by historian and Syme Family documentarian Veronica Condon. The copy I saw was in SLV Special Collections, and the Polaroids are well preserved

Mabel Young does not appear to have worked in ceramics; I'd suggest that multimedia artist and craftswoman Christian Waller is a candidate for this work. Like Mabel, her status and work as an artist was formidably overshadowed by her husband Napier[6].

Unlike Mabel’s legacy – which is hard to trace and not voluminous - we do have a significant amount of Christian's work in the archival and historical record, particularly through her stained glass windows.

My hope is that this article will be shared around the descendant families of all the people historically associated with the monument, and perhaps someone somewhere will have a note, a diary entry, a receipt or a piece of information that will contribute to a better understanding of one of the most illustrious and sophisticated examples of Egyptiansing architecture in the world.

A Melbourne Enchantment: David And Annabella Syme's House Of Eternity

Acrylic on canvas, 54" x 54", July 2024

Setken is an artist who specialises in Egyptomania and Ancient Egyptian religious themes and iconography.

His paintings have been featured in two academic Egyptological books, including on a cover, and his paintings have found their way into significant Australian private art collections.

He was most recently a featured artist in Volume 6 of Jimmy Hornet Magazine.

Photo of the author at the tomb courtesy Anthea Palmer / Jimmy Hornet Magazine

[1] Being presented at the Melbourne Theosophical Society in April 2025, the PMI Library and Kew Library in October 2025; further venues and dates are currently being confirmed

[2] The degree to which David Syme had insight into this topic has not yet been published, and is discussed in the new version of my talk.

[3] Blamire Young was an enormously popular water colourist; there is a retrospective of his work at Mildura Arts Centre in 2025. Coincidentally he was a fan of the work of Christian Waller mentioned at the end of the article.

[4] State Library Victoria, special collections Box 1180/5 (d), MS9751/277-349.

[5] Architectural historians reading this may quite rightly be asking, “Did you investigate the tiles of the Tessellated Tile Company?”, which was the go to for all ceramic tiles of the day. The answer is yes. Melbourne University Special Collections have their large and fragile ledgers of all business for the day, and there is no record of Butler and Bradshaw, Young, or the Ballantines having engaged with them from the time David Syme died to after 1910 when the monument was completed.

[6] I am aware that Christian would have been very young at the time that the tomb was being completed, however, it is recorded that in 1909 she came to Melbourne to study at the National Gallery School, which is where she met Napier whom she married 5 years later. Napier Waller is most famous for his sophisticated War Memorial Monument in Canberra.

Comments